Bits, bytes, and memory addressing

In lesson 1.3 -- Introduction to objects and variables, we talked about the fact that variables are names for a piece of memory that can be used to store information. To recap briefly, computers have random access memory (RAM) that is available for programs to use. When a variable is defined, a piece of that memory is set aside for that variable.

The smallest unit of memory is a binary digit (also called a bit), which can hold a value of 0 or 1. You can think of a bit as being like a traditional light switch -- either the light is off (0), or it is on (1). There is no in-between. If you were to look at a random segment of memory, all you would see is …011010100101010… or some combination thereof.

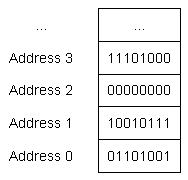

Memory is organized into sequential units called memory addresses (or addresses for short). Similar to how a street address can be used to find a given house on a street, the memory address allows us to find and access the contents of memory at a particular location.

Perhaps surprisingly, in modern computer architectures, each bit does not get its own unique memory address. This is because the number of memory addresses is limited, and the need to access data bit-by-bit is rare. Instead, each memory address holds 1 byte of data. A byte is a group of bits that are operated on as a unit. The modern standard is that a byte is comprised of 8 sequential bits.

Key insight

In C++, we typically work with “byte-sized” chunks of data.

The following picture shows some sequential memory addresses, along with the corresponding byte of data:

As an aside…

Some older or non-standard machines may have bytes of a different size (from 1 to 48 bits) -- however, we generally need not worry about these, as the modern de-facto standard is that a byte is 8 bits. For these tutorials, we’ll assume a byte is 8 bits.

Data types

Because all data on a computer is just a sequence of bits, we use a data type (often called a type for short) to tell the compiler how to interpret the contents of memory in some meaningful way. You have already seen one example of a data type: the integer. When we declare a variable as an integer, we are telling the compiler “the piece of memory that this variable uses is going to be interpreted as an integer value”.

When you give an object a value, the compiler and CPU take care of encoding your value into the appropriate sequence of bits for that data type, which are then stored in memory (remember: memory can only store bits). For example, if you assign an integer object the value 65, that value is converted to the sequence of bits 0100 0001 and stored in the memory assigned to the object.

Conversely, when the object is evaluated to produce a value, that sequence of bits is reconstituted back into the original value. Meaning that 0100 0001 is converted back into the value 65.

Fortunately, the compiler and CPU do all the hard work here, so you generally don’t need to worry about how values get converted into bit sequences and back.

All you need to do is pick a data type for your object that best matches your desired use.

Fundamental data types

The C++ language comes with many predefined data types available for your use. The most basic of these types are called the fundamental data types (informally sometimes called basic types or primitive types).

Here is a list of the fundamental data types, some of which you have already seen:

| Types | Category | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| float double long double |

Floating Point | a number with a fractional part | 3.14159 |

| bool | Integral (Boolean) | true or false | true |

| char wchar_t char8_t (C++20) char16_t (C++11) char32_t (C++11) |

Integral (Character) | a single character of text | ‘c’ |

| short int int long int long long int (C++11) |

Integral (Integer) | positive and negative whole numbers, including 0 | 64 |

| std::nullptr_t (C++11) | Null Pointer | a null pointer | nullptr |

| void | Void | no type | n/a |

This chapter is dedicated to exploring these fundamental data types in detail (except std::nullptr_t, which we’ll discuss when we talk about pointers).

Integer vs integral types

In mathematics, an “integer” is a number with no decimal or fractional part, including negative and positive numbers and zero. The term “integral” has several different meanings, but in the context of C++ is used to mean “like an integer”.

The C++ standard defines the following terms:

- The standard integer types are

short,int,long,long long(including their signed and unsigned variants). - The integral types are

bool, the various char types, and the standard integer types.

All integral types are stored in memory as integer values, but only the standard integer types will display as an integer value when output. We’ll discuss what bool and the char types do when output in their respective lessons.

The C++ standard also explicitly notes that “integer types” is a synonym for “integral types”. However, conventionally, “integer types” is more often used as shorthand for the “standard integer types” instead.

Also note that the term “integral types” only includes fundamental types. This means non-fundamental types (such as enum and enum class) are not integral types, even when they are stored as an integer (and in the case of enum, displayed as one too).

Other sets of types

C++ contains three sets of types.

The first two are built-in to the language itself (and do not require the inclusion of a header to use):

- The “fundamental data types” provide the most the basic and essential data types.

- The “compound data types” provide more complex data types and allow for the creation of custom (user-defined) types. We cover these in lesson 12.1 -- Introduction to compound data types.

The distinction between the fundamental and compound types isn’t all that interesting or relevant, so it’s generally fine to consider them as a single set of types.

The third (and largest) set of types is provided by the C++ standard library. Because the standard library is included in all C++ distributions, these types are broadly available and have been standardized for compatibility. Use of the types in the standard library requires the inclusion of the appropriate header and linking in the standard library.

Nomenclature

The term “built-in type” is most often used as a synonym for the fundamental data types. However, Stroustrup and others use the term to mean both the fundamental and compound data types (both of which are built-in to the core language). Since this term isn’t well-defined, we recommend avoiding it accordingly.

A notable omission from the table of fundamental types above is a data type to handle strings (a sequence of characters that is typically used to represent text). This is because in modern C++, strings are part of the standard library. Although we’ll be focused on fundamental types in this chapter, because basic string usage is straightforward and useful, we’ll introduce strings in the next chapter (in lesson 5.7 -- Introduction to std::string).

The _t suffix

Many of the types defined in newer versions of C++ (e.g. std::nullptr_t) use a _t suffix. This suffix means “type”, and it’s a common nomenclature applied to modern types.

If you see something with a _t suffix, it’s probably a type. But many types don’t have a _t suffix, so this isn’t consistently applied.